The story of Star Wars carries a pulse beneath the starfighters and sabers. Strip away the spectacle and what remains is a myth about fathers and sons. At the center stands Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, a son and father whose struggle moves beyond blood. Their bond defines the emotional architecture of the saga.

Luke inherits a shadow he did not choose. Vader becomes his own myth, then his son’s greatest fear.

This essay examines how Star Wars uses fatherhood and legacy to tell stories that echo the psychological patterns described by Carl Jung. His ideas about the Father archetype, the Shadow, and individuation give us a useful language for why these relationships resonate.

The aim is not to force Jung onto the text. The films and series often move through patterns Jung mapped long before Luke looked across Tatooine’s twin suns.

Luke’s journey is not only a rebellion against an empire. It is a rebellion against the gravitational pull of inheritance. His confrontation with Vader is as much internal as it is physical.

In the cave on Dagobah, when Luke sees his own face behind Vader’s mask, the story speaks in Jungian terms. The enemy is not only outside. It lives within. Luke must recognize the darkness inside him, accept that it exists, and refuse to be consumed by it. That vision sets the terms for everything that follows.

Around this mythic spine, other bonds deepen the theme. Han Solo and Ben Solo fracture under guilt and unreachable love. Jango Fett and Boba Fett wrestle with legacy through blood and vengeance, not the Force. Obi-Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker show how surrogate fatherhood can guide and still fail.

Din Djarin and Grogu offer a rare answer to darker patterns by choosing family rather than inheriting it. These are not clean tales of good fathers and bad sons. They are uneasy negotiations between past and future. Each father figure casts a shadow. Each son decides to step into it, to escape it, or to burn it away.

Vader and Luke, The Confrontation with the Father

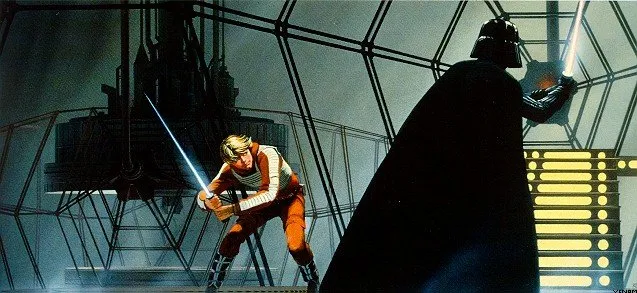

The bond between Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader sits at the center of the Star Wars myth. Everything spirals outward from it. Their story is not only about war, rebellion, or the Force. It is about the moment a son must face the figure who shaped his fate before he understood it.

On Cloud City, Vader’s revelation lands with mythic force.

Luke must confront who his father is, and what that makes him. Jung described the Father archetype as both guide and barrier, a figure one must face to become whole.

For Luke, Vader is both the literal father and the symbolic obstacle, the source of life and the embodiment of a dark power he must reckon with to claim his own identity.

Luke’s refusal to join him is not simple rejection. It is the first act of individuation, the process Jung saw as essential to psychological growth. Luke refuses to be absorbed into his father’s shadow.

He falls, broken and bloodied, yet he falls as himself. This is a different kind of heroism.

Not the triumph of brute strength, but the refusal to inherit a corrupted legacy.

Years later, on the second Death Star, Luke faces Vader again. The conflict is layered now. He knows the truth of the Force, of his lineage, of the man behind the mask. When the Emperor tempts him, Luke’s rage explodes in a flurry of blows.

For a moment he gives in to the darkness he feared on Dagobah. His blade carves into the thin line separating son from father. When he stops, breathing hard, Luke recognizes the reflection staring back.

That choice, to throw down his weapon, completes his Jungian journey.

Luke does not destroy his father to become free of him.

He accepts what Vader represents, then refuses to be defined by it. Jung argued that real growth requires integration of the Shadow, not its erasure. Luke’s mercy is strength, not weakness.

It is the moment he fully claims himself.

For Vader, the confrontation becomes a mirror. He sees in his son the light he buried. He is not redeemed by destiny.

He moves because his son holds up a mirror and will not let him disappear behind the mask.

In that instant the saga stops being grand myth and becomes human, a father reaching for the last shard of who he used to be because his son believes it is still there.

The Cave of Dagobah, Meeting the Shadow

Before Luke can face Darth Vader, he must face himself. That is what the cave on Dagobah reveals. It is one of the quietest scenes in The Empire Strikes Back, and one of the most important. Under Yoda’s watch, Luke steps into a place that feels alive with more than danger. It is the symbolic descent Jung described often, the inward journey before the outward one.

When Vader appears in the vision, Luke strikes without thinking. The mask falls. His own face stares back.

It is clean and chilling.

Jung defined the Shadow as the disowned part of ourselves, the darkness carried in the unconscious. Luke does not only see his father. He sees the possibility of becoming him. The inheritance becomes explicit. The darkness is not waiting somewhere else. It is already inside.

The cave reframes everything.

The real battle is not only between Luke and the Empire. It is between Luke and the temptation to mirror his father’s fall. Yoda does not explain it away. He lets the vision speak. In that silence, Jung’s insight settles. To grow, one must look directly at the parts of the self that are hardest to face.

The cave is not prophecy. It is potential. Jung believed that confronting the Shadow is essential to individuation. If ignored, the Shadow grows in secret, twisting into something destructive.

|

| Here's looking at yourself, kid |

If acknowledged, it can be integrated, becoming a source of strength. Luke does not understand this fully yet. The image of his face beneath Vader’s mask stays with him like a splinter.

Mirrors and Variations, Other Father and Son Dynamics

Luke and Vader form the saga’s axis, but Star Wars fills its worlds with variations. Some are tragic. Some redemptive.

Others twist the pattern into ambiguity. Through these, the series explores the Father archetype and the many ways sons respond to it.

Han Solo and Ben Solo

Their bond echoes Luke and Vader, stripped of mythic clarity.

Han is not a Chosen One.

He is a father trying to reach a son he barely understands. Ben’s turn to the dark is born of fracture, manipulation, and guilt. The patricide on Starkiller Base is a textbook attempt to destroy the father’s authority and seize identity.

Freedom does not follow.

A ghost does.

Han remains as conscience and regret. The confrontation fails to integrate anything.

Ben spends his arc battling the echo of a father he could not truly kill.

Jango Fett and Boba Fett

One of the few dynamics untouched by the Force. Boba is Jango’s unaltered clone, raised as a son and a continuation of the father himself. Jung wrote that sons often inherit unexamined complexes.

For Boba that inheritance is literal. His youth mirrors Jango’s path of bounty and violence.

In The Book of Boba Fett he slowly steps out from his father’s shadow, building a code that is his own. The confrontation is not with a living father, but with a legacy that must be reshaped.

Obi-Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker

Surrogate fatherhood forged by duty and love. After Qui-Gon Jinn’s death, Obi-Wan raises Anakin as student and son figure. Their bond breaks in fire on Mustafar in Revenge of the Sith.

Obi-Wan’s plea is not only a master’s lament.

It is a father losing a son to his shadow. When the son is pulled under by the unconscious, Jung reminds us, the father becomes witness and collateral.

The tragedy embodies that warning.

Luthen Rael and Cassian Andor

In Andor, affection does not drive the bond. Survival and strategy do. Luthen sees in Cassian the potential Self, not yet formed.

He forges him into a weapon. This is fatherhood as calculation.

The Father archetype here is not nurturing, it is instrumental. Cassian’s individuation arrives when he steps beyond what Luthen tried to make of him.

Din Djarin and Grogu

In a galaxy of fathers who wound or control, Din chooses to love. He is not bound by blood, destiny, or prophecy.

He chooses the child, and the child chooses him.

The pattern flips.

Instead of inheritance or rebellion, the bond is mutual shaping. Fatherhood becomes a shared path. Jung spoke of the Father as burden and guide. Here it becomes chosen belonging.

The Dark Father Archetype, Palpatine’s Shadow Empire

Every myth has a figure who claims the role of father while offering no true inheritance. In Star Wars that figure is Sheev Palpatine. He stands not as guide, but as devourer. Jung described false fathers who claim authority to consume and control. Palpatine embodies that truth.

He seduces Anakin with flattery, fear, and promises of control over death. He becomes a dark surrogate father who offers mastery at the price of the self.

This is not relationship, it is possession.

Palpatine does not nurture sons.

He manufactures heirs.

Decades later he repeats the pattern with Ben Solo, wearing the mask of Snoke. He preys on insecurity and shame. Jung’s Terrible Father archetype lives here, the devouring figure who offers a false path to power in exchange for the person you are.

In Star Wars that bargain leads to ruin every time.

Unlike Han, unlike Luke, Palpatine does not cast a personal shadow, he is the shadow. Anakin becomes Vader. Ben becomes Kylo Ren. Each must face the truth that the father they followed was never a father at all.

This is why defeating Palpatine is more than removing a villain. It is breaking a psychic chain. Luke integrates the shadow he sees in Vader. Anakin succumbs to Palpatine’s shadow, then breaks from it at the end.

Ben drifts toward it, then claws his way back. One shadow can be integrated.

The other must be severed.

Jungian Themes Across the Stars...

Across films and series, Star Wars returns to one question.

What does a son inherit from his father, and what can he choose for himself. Jung provided a language for this tension. Archetype, shadow, individuation. These ideas explain why the father and son stories echo across generations of viewers.

The core bond, Luke and Vader, maps clearly to the heroic confrontation with the Father. Luke faces a man and the shadow that comes with him.

By refusing to destroy his father and by confronting darkness with clarity, Luke models growth through integration rather than annihilation.

Other arcs fracture the pattern. Ben Solo tries to sever his inheritance with violence, then learns that absence does not equal freedom.

Boba Fett inherits a violent complex and slowly reshapes it into a code.

Cassian Andor is forged by Luthen Rael, then steps outside that mold.

Din Djarin shows fatherhood as conscious choice, not fate.

Palpatine remains the devouring father.

His presence clarifies why Luke’s mercy matters. One kind of shadow belongs to the self and can be integrated. The other arrives as domination and must be rejected. These tales do not offer a single moral.

Jung warned against turning archetypes into rigid laws. They are patterns, not commandments.

Conclusion

Every myth comes home. Star Wars may range across distant stars, yet its beating heart is intimate.

Fathers and children.

Shadows and light.

Luke facing Vader, not simply adversary and savior, but two halves of a broken line that must be mended or severed.

Dagobah sets the hinge. Luke’s face behind Vader’s mask turns a galactic war into a personal reckoning with the Shadow. He does not win by destroying his father. He wins by recognizing the darkness and refusing to become it.

Mercy becomes strength. Identity hardens into choice.

Around that center, the variations keep faith with the theme. Ben tries to cut away his inheritance and finds only echoes. Boba carries Jango’s weight, then builds a life of his own.

Cassian grows beyond the man who made him a weapon. Din and Grogu show that fatherhood can be chosen and healing. Palpatine, the false father, offers power and consumes the self. Breaking from him is not only rebellion. It is freedom of the psyche.

Jung wrote that a son must face the father to grow. Not to destroy or obey, but to confront, to integrate, to stand apart. Star Wars holds that truth in many shapes.

Some paths lead to ruin.

Some to redemption.

Many remain unresolved.

The constant is the inner landscape, shadow, inheritance, choice. Every father casts a shadow. Every child decides where it ends. Somewhere between fear and love, between legacy and identity, a person becomes who they are.

Beneath all the starships and lightsabers, that is the story Star Wars keeps telling.