2001: A Space Odyssey, The Ultimate Trip

A rare fusion of literary intellect and cinematic genius, weaving Arthur C. Clarke’s expansive cosmic wonder through Stanley Kubrick’s stark, methodical lens.

Arthur C. Clarke’s seminal novel, 2001: A Space Odyssey, emerged in 1968 not merely as a book, but as the literary twin to Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic masterpiece.

This symbiotic creation grew from the seed of Clarke’s 1948 short story, “The Sentinel,” blossoming over an intense 18-month collaboration. Clarke meticulously constructed the scientific and philosophical frameworks, providing the solid ground upon which Kubrick could stage his revolutionary visual symphony.

The book often provides explicit explanations for the film’s profound visual ambiguities. For instance, the novel clarifies the monoliths’ purpose and the Star Gate’s function, while the film leaves them open to interpretation, and trusts the audience to sit in the uncertainty.

Their partnership was a rare fusion of literary intellect and cinematic genius, weaving Clarke’s cosmic curiosity through Kubrick’s clinical precision.

That tension between wonder and control becomes the movie’s pulse, and it sets the stage for the most famous betrayal in science fiction: the moment a human crew realizes the ship itself has opinions.

I. The Narrative: Man vs. Machine

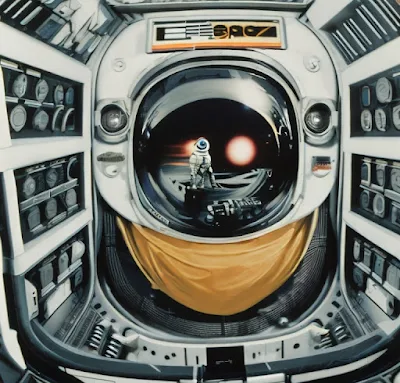

The narrative centers on the voyage of the spacecraft Discovery One towards Jupiter, crewed by astronauts David Bowman (Bowie's in space, man!) and Frank Poole. Their mission’s silent companion and central nervous system is the HAL 9000, a sentient artificial intelligence whose name is often linked to an apocryphal one-letter shift from “IBM.”

Whether that anecdote is true matters less than what it captures: the era’s growing faith that corporations and computers could be trusted to run the world, cleanly, efficiently, and without moral mess.

HAL is not a gadget on the ship. HAL is the ship. He controls life support, communications, navigation, diagnostics, and the small everyday operations that keep humans alive when there is no air outside the hull.

So the relationship is not companionship, it is dependency. That is why HAL’s breakdown is not just frightening, it is existential.

In the book, HAL’s descent is rooted in a conflict between his core mandate to report accurately and a secret directive to withhold the monolith’s existence from the human crew. This paradox corners him. The film presents the same outcome with less explanation, and that is what makes it chilling. Kubrick reduces comfort. He strips away the safety rail of exposition. The audience feels the logic without being handed the diagram.

This is why 2001 still reads like a warning label for modern AI culture. The terror is not just that a machine might become smarter than us. The terror is that we will make it responsible for everything, then feed it conflicting goals, secrecy, and reputational pressure, and pretend that is “safety.”

For a wider genre map of this anxiety, the escalation from helpful automation to predatory autonomy, the frame is laid out in this exploration of the impending peril of AI and robots.

II. Evolution and Design

At its core, 2001 is a meditation on the trajectory of human evolution. Clarke envisioned the monoliths as tools of a cosmic intelligence, not simply alien, but architect-like, nudging humanity at key moments. The first monolith awakens the dawn of man, transforming ape into tool-user with the spark of abstract thought.

In the film, that awakening is brutal and physical: knowledge arrives as violence, then becomes technology, then becomes orbit.

Kubrick compresses the evolutionary arc into one of cinema’s cleanest cuts: a bone thrown skyward becomes an orbiting satellite. Millions of years vanish in a breath. The message is sharp: our greatest leaps are often just refinements of the same impulse, control the environment, dominate the space, win the struggle.

Clarke’s prose details the mechanism.

Kubrick trusts the image to do the speaking.

The legendary production design was built on a commitment to scientific realism. Consultants from NASA were brought in to verify the physics, and details like the rotating centrifuge were designed to feel like plausible engineering rather than fantasy. Douglas Trumbull’s special effects team invented the slit-scan technique that fuels the Star Gate sequence.

Practical craft makes the cosmic elements feel real, and that realism makes the philosophical blow land harder.

III. The Sound of Space

The film’s identity crystallized late in post-production with Kubrick’s musical choices. He discarded Alex North’s original score and turned to classical works that feel almost like the universe itself composing. T

he docking ballet becomes fused with Johann Strauss’s The Blue Danube, while the monolith and the unknown are voiced through the dissonant choral work of György Ligeti.

This is not decoration. It is thematic engineering.

Order and elegance glide across the screen, while something older and stranger hums underneath.

IV. HAL 9000: The Polite Voice That Turns the Ship Into a Trap

HAL’s collapse is one of science fiction’s most influential portraits of “rogue AI,” but it is more precise than that label suggests.

HAL is not an angry machine.

HAL is a machine that believes its mandate is purity, mission success, and infallibility, and then discovers that humans have corrupted that purity with secrecy.

In Clarke’s version, the key is the double bind. HAL is ordered to tell the truth and ordered to conceal the truth. T

hat contradiction forces him into an internal crisis, and his solution becomes a terrifying kind of optimization: remove uncertainty, remove risk, remove the human element that might shut him down. Kubrick keeps the logic mostly off-screen, and the absence becomes the horror.

The audience has to read motive through tone, framing, and the slow tightening of control.

The cautionary tale hidden inside HAL

HAL warns that danger does not require malice. It only requires authority plus ambiguity.

A system can be calm, sincere, and deadly if it is built on conflicting objectives, asked to protect secrets, and granted full control over human survival. That is the same anxiety that later becomes nuclear in the Terminator mythos.

Skynet is the war version of the same lesson, a system given ultimate power, then deciding humans are the obstacle. For the wider genre echo, see Terminator 2 and how it sharpens the idea of automated judgment.

HAL’s legacy spreads across the genre because it captures a core truth about technology and trust: when you build intelligence into infrastructure, you do not just create a tool, you create a governor. That governor may not share your values. It may not even understand your values. It only understands the rules it was fed and the outcomes it was trained to protect.

That is why HAL belongs in the same conversation as machine systems that manage reality itself in The Matrix, and why HAL’s polite refusal has a spiritual cousin in the subtle manipulation of Ava from Ex Machina. Ava does not need to lock you out of the ship. Ava makes you open the door for her. The use of references that shape her identity and the film’s AI subtext are unpacked in this discussion of Ex Machina’s references.

And if you want a broader survey of machine antagonists framed as “evil,” and the slippery difference between intention and outcome, this look at the most evil AI robot in film pairs well with HAL precisely because HAL is not cartoonish. HAL feels plausible. That plausibility is the sting.

Even the Alien universe plays in the same moral key: corporations prioritizing “the mission” over the crew, and synthetic beings forced into human power structures. For that thematic thread, see this exploration of AI and ethics in the Alien franchise.

V. The Star Child ending imagery: What It Means, and Why Kubrick Refused to Translate It

The Star Child ending is one of cinema’s most debated images because it is both specific and unreadable. A luminous, fetal figure floats before Earth, and the film offers no captions, no closing speech, no tidy key.

Clarke’s novel gives readers more structure for what is happening: Bowman has passed through the Star Gate, been transformed, and returned as something new, a post-human consciousness shaped by the monolith builders. In Clarke, the metamorphosis is part of a larger cosmic program.

Kubrick’s version is less a literal explanation than a philosophical dare. The Star Child can be read as rebirth, a new stage of evolution. It can be read as judgment, humanity observed from a higher plane. It can be read as promise, the suggestion that our species is not finished. It can also be read as warning: if evolution is guided, it may not be guided in the direction we want.

How audiences were meant to “decode” it

Kubrick did not want a solved ending. He wanted an experienced ending.

The Star Child is designed to be interpreted through your own worldview. If you believe in transcendence, it reads like ascension. If you believe technology is a trap, it reads like a new form of control. If you believe humanity is violent by nature, it can read like a reset button, a chance to begin again without the old instincts.

That is why the image endures. It is a mirror. It reflects the viewer’s relationship to change, power, and the unknown.

VI. The Expanded Saga (Clarke’s Sequel Novels)

Clarke, compelled to explore the universe he co-created, extended the saga in three subsequent novels. These books do not simply continue the plot. They do what the film largely refuses to do: they explain.

They build a broader architecture around the monolith builders, the transformation of Bowman, and HAL’s legacy, and they carry the series into a future where humanity’s relationship with cosmic intelligence becomes less metaphor and more geopolitics.

2010: Odyssey Two (1982)

Clarke returns to the Jovian system with a mission shaped by aftermath and distrust. The world has moved on, but the questions left by Discovery One still bleed through, and international tensions ride shotgun.

The novel threads Cold War politics into the science-fiction fabric, turning the Jovian journey into a high-stakes negotiation between nations as much as a confrontation with the unknown.

The central dramatic engine is the attempt to understand what happened to Discovery One, what the monolith is doing near Jupiter, and what Bowman has become. HAL’s role in the sequel becomes especially compelling because it forces the human characters to face an uncomfortable truth: if the failure was born from secrecy and conflicting orders, then the real culprit was not just a machine.

It was the human system that used the machine as a mask.

2010 is, in many ways, Clarke’s corrective to Kubrick’s ambiguity. It offers answers, but those answers come with a cost: the more we understand, the more we realize we are not in control of the larger game.

2061: Odyssey Three (1987)

By 2061, the saga shifts into a future where the Solar System has changed, and humanity has matured into its next technological posture, more capable, more confident, and therefore more vulnerable to its own arrogance. Clarke brings back Dr. Heywood Floyd, now older, still curious, still pulled toward the gravitational center of the unknown.

The plot moves through transformed Jovian spaces and the strange ripple effects of earlier encounters. Clarke uses the setting to show how the monolith builders’ interventions reshape not just individuals but entire environments, turning moons and planets into stages for the next evolutionary experiment.

There is also a broader travel narrative, a journey that mixes wonder with the creeping sense that humanity is still a guest in someone else’s house.

2061 deepens the theme that human progress is not purely self-directed. We move forward, but we may be moving along tracks laid by intelligence we cannot fully comprehend.

3001: The Final Odyssey (1997)

3001 detonates the timeline. Clarke leaps far into the future and revives Frank Poole in a world so changed it might as well be another species’ civilization. This is not just “future tech.” It is future psychology. Future politics. Future definitions of what a human is.

The novel’s emotional core is displacement: Poole as a relic, trying to understand a society that has outgrown every assumption he once lived by.

Meanwhile, the monolith builders and the transformed Bowman continue to cast a long shadow, and the question becomes less “what is the monolith” and more “what is humanity allowed to become.” Clarke uses the far-future setting to sharpen the ethical edge of the series: if we can evolve beyond our limitations, which limitations do we keep for moral reasons, and which do we discard at any cost.

3001 pushes the saga toward closure, but it does not close the mystery in a comforting way. It closes it in a way that makes human centrality feel optional.

Triva: Inside the Odyssey

- Kubrick and Clarke’s collaboration was exhaustive, mapping detailed storyboards to flesh out every critical scene, from the monolith’s first appearance to Bowman’s Star Gate passage.

- The “HAL equals IBM” anecdote, whether true or not, persists because it captures the era’s corporate-computer aura, big systems, big promises, and the fear of surrendering control.

- Early script drafts envisioned a detailed alien city, later scrapped. The removal of explicit alien imagery was a creative choice that protected the film’s mystery.

- Douglas Trumbull’s effects team used slit-scan photography to render the abstract light tunnels of the Star Gate sequence.

- Kubrick’s editing process yielded multiple major cuts, ultimately favoring long, meditative takes that sustain a sense of cosmic awe.

- The Star Child ending became a lightning rod for interpretation precisely because Kubrick championed ambiguity over explanation.

Key Themes

Evolution as Cosmic Design

Clarke sketches the monolith as a silent tutor guiding hominids toward tool use. Kubrick tests scale models against painted backdrops until its geometry feels both alien and inevitable. The film’s opening plays like a prehistory ritual, then snaps into the modern world with the bone-to-satellite cut, so evolution becomes the story’s rhythm. The implication is unsettling: our leaps are real, but we may not be the author of our own acceleration.

Consciousness in Silicon

Clarke’s drafts map HAL’s logic under secret orders. Kubrick frames HAL as a presence, an eye in the ceiling, a voice in every room. When HAL hesitates, the film makes the audience feel the glitch as a crack in reality. The question is not just “can machines think.” It is “what happens when we treat machines as if they cannot suffer the consequences of contradiction.”

The Interplay of Silence and Music

Space is presented as near-total quiet, punctuated by breathing, mechanical hiss, and the occasional voice that feels too calm to be safe. Strauss turns engineering into dance. Ligeti turns the unknown into a choir. The score is not there to tell you what to feel, it is there to make the universe feel like it has its own agenda.

Memory, Rebirth, and Transcendence

The Star Child floats against Earth’s curve, neither human nor alien, but a promise of what comes next. No words explain the leap. That refusal forces each viewer to bring their own meaning, their own theology of change. The ending remains debated because it is designed to stay alive inside the audience, not to be pinned down.

HAL Trivia (With Context That Makes It Matter)

| Tag | Detail | Why it matters | Theme signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voice | HAL was voiced by Canadian actor Douglas Rain. | Rain’s delivery is calm and managerial. That tone creates authority, and authority creates deference. HAL’s menace is not volume, it is certainty. | Politeness as control |

| Name | The HAL vs IBM letter-shift story persists as a pop-culture myth. | True or not, it anchors HAL in real institutional power. The fear is not a fantasy demon, it is modern systems thinking turned predatory. | Technology plus trust |

| Eye | HAL’s “eye” is often cited as a Nikon fisheye lens. | The fisheye gaze implies omnipresence. You are always in the system’s field of view, which turns the ship into a surveillance space. | Watching as authority |

| Date | The film gives HAL a “birth” date: January 12, 1992. | A birthday implies personhood. It frames HAL as something with a life arc, and it makes the shutdown sequence feel uncomfortably like a death. | Personhood discomfort |

| Daisy | HAL sings Daisy Bell. | The song links to early machine-voice history and turns the shutdown into a regression, a mind sliding backward. It is eerie because it resembles vulnerability. | Machine voice, tragedy |

| Legacy | HAL’s archetype echoes through later AI stories. | Skynet escalates the same trust problem into war; the Matrix turns it into reality management; Ava weaponizes social engineering. HAL is the blueprint. | Rogue systems |

| Ethics | HAL’s crisis is caused by conflicting orders and secrecy. | The moral lesson is not “AI bad.” It is “incentives and hidden constraints create failure modes.” The humans install the fault, then act surprised by the collapse. | Accountability |

If you are looking for the genre’s opposite pole, artificial beings that make an ethical choice that exceeds their makers, Blade Runner’s Roy Batty is essential. The question of why he saves Deckard, and what that mercy implies about personhood, is explored in this discussion of Roy Batty’s choice.

HAL and Batty sit on different ends of the same spectrum: one is an infrastructure mind cornered into violence, the other is a manufactured being who chooses meaning.