Time Travel Paradoxes

The classic traps, the modern fixes, and why science fiction keeps walking into them on purpose.

Time travel paradoxes have been a source of fascination and confusion for decades, both in science fiction and real-world physics.

Let’s explore some of the most well-known types of paradoxes and provide examples from popular movies and books.

Before we get specific, it helps to name the underlying problem most paradoxes share: causality wants a clean chain, but time travel knots the chain into a loop. Once an effect can reach back and touch its own cause, stories have to choose a rule set. Some stories let timelines overwrite. Some branch. Some enforce “whatever happened, happened.” Some treat time like a road you can drive, others like a lake where you can only disturb the surface.

Most time travel fiction is really a debate between three models: a single mutable timeline (change the past, rewrite the present), a single self-consistent timeline (you can go back, but you cannot produce contradictions), and many-worlds branching (your intervention creates a new track). The paradox is often just the pressure test that reveals which model the story is using.

The Grandfather Paradox

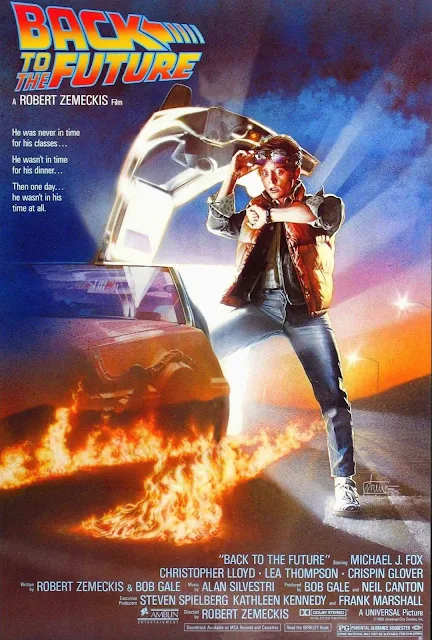

One of the most famous paradoxes is the Grandfather Paradox. It posits that if you travel back in time and kill your own grandfather before he has children, you would never have been born, which means you couldn’t have gone back in time to kill him in the first place. This paradox has been explored in many works of fiction, including the movie "Back to the Future." In the film, Marty McFly travels back in time and accidentally interferes with his parents' meeting, endangering his own existence.

Nature of the paradox: a direct logical contradiction in the premise “the traveler exists.” The trip depends on the traveler being born, but the traveler’s action removes the conditions for that birth. Cause eats effect, and the loop becomes self-negating.

Common story fixes: the universe blocks the contradiction (you cannot do it), the timeline overwrites and the traveler fades, the act creates a new branch where you do not come from that line, or the timeline is self-consistent and your attempt always fails because history already includes that failure.

The Bootstrap Paradox

The Bootstrap Paradox occurs when an object or information is brought back in time from the future and becomes the origin of its own creation. In the novel "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," Harry and Hermione use a Time-Turner to save Sirius Black from execution. However, it is revealed later that Harry's patronus charm, which saved them from danger, was the same one he saw earlier, leading to the question of who originally cast it.

Nature of the paradox: not contradiction, but missing origin. The loop can be internally consistent, yet it contains an object or idea with no first author. It exists because it exists, a closed causal circle where “creation” is replaced by “circulation.”

Why it matters in fiction: bootstrap loops turn destiny into something eerie and practical. They also turn agency into a delayed recognition, the moment you realize the “outside help” was your own future action coming back around.

The Predestination Paradox

The Predestination Paradox is the idea that events in the past have already happened and cannot be changed, meaning that any attempt to do so would ultimately lead to those events occurring in the first place. In the movie "12 Monkeys," a time traveler named James Cole attempts to stop a deadly virus from wiping out humanity by traveling back in time. However, his actions end up inadvertently causing the outbreak, revealing that the events were predetermined all along.

Nature of the paradox: prevention becomes causation. The traveler’s “fix” is one of the mechanisms that produces the very event they are trying to stop. It is the most cruel version of a loop because it uses intention as fuel for inevitability.

How stories make it land: predestination paradoxes are tragedies in sci-fi clothing. They turn knowledge into a cage, and they force a question that hurts: if you cannot change the outcome, what is the moral meaning of trying?

The Butterfly Effect

This example of chaos theory posits that small changes in the past can have drastic consequences in the future. In the movie "The Butterfly Effect," a man named Evan travels back in time to change his past and fix his troubled life. However, each change he makes leads to unintended and disastrous consequences.

This theory is based on chaos theory, which suggests that small changes can have large effects on complex systems.

Nature of the paradox: the control illusion. You can change the past, but the system is too complex to steer with confidence. Each “repair” changes the context that made the repair seem necessary, so the traveler is constantly solving yesterday’s problem in a world that no longer exists.

Why it keeps showing up: this is the paradox that punishes wishful thinking. It frames time travel as a moral hazard, because the smallest act of “help” can become a large-scale harm you did not foresee.

The Information Paradox

This paradox arises from the possibility of bringing information from the future back to the past. It is related to the Grandfather Paradox and questions whether the mere act of conveying information back in time could create a paradox that would prevent the information from ever having been created in the first place.

In the Terminator films, the character John Connor sends a message back in time to his mother Sarah, warning her about the impending danger of the Terminator. However, the message ends up being a key factor in the creation of the very technology that led to the Terminator's creation.

Nature of the paradox: a bootstrap loop made of knowledge. The timeline contains instructions or warnings that exist without a clear first author, and those instructions change decisions in the past that help create the future they came from.

What it tests: responsibility. If the warning is part of the cause, then the act of trying to prevent the future is also an act of building it. That tension, between caution and manufacture, is why information paradoxes feel like prophecy with a feedback circuit.

The Multiple Timelines Paradox

The Multiple Timelines Paradox occurs when time travel creates a branching timeline, in which events that occur in the past create a new timeline that runs parallel to the original.

This paradox is explored in the movie "Avengers: Endgame," where the Avengers use time travel to retrieve the Infinity Stones and undo the events of the previous movie. Their actions create new timelines, which they must then navigate in order to prevent unintended consequences and preserve the integrity of their own timeline.

Nature of the paradox: it avoids contradiction by multiplying reality, but it creates an identity and ethics problem. If every intervention spawns a new world, what does it mean to “undo” anything? You may save one timeline while causing trauma, loss, or instability in another you created as collateral.

Why it matters: branching turns time travel into world-making. The paradox is not whether the logic works, it is whether the traveler can live with the moral spillover of their “fix.”

Physicist Kip Thorne, who was a consultant on the movie "Interstellar," has said that time travel to the past is unlikely to be possible, as it would require the existence of negative energy densities and the ability to create a stable wormhole through space-time. However, he has also suggested that time travel to the future could be possible, through the use of time dilation and the effects of gravity on the flow of time.

Famous physicist Stephen Hawking once said, "Time travel used to be thought of as just science fiction, but Einstein's general theory of relativity allows for the possibility that we could warp space-time so much that you could go off in a rocket and return before you set out."

In conclusion, time travel paradoxes offer a fascinating exploration of the nature of time and the implications of changing the past. While they may seem like purely fictional concepts, they are grounded in real-world physics and raise thought-provoking questions about the nature of causality and the limits of human knowledge. As technology and our understanding of the universe continue to evolve, it will be interesting to see how these paradoxes are explored and understood in the future.

The greatest time travel mind-bender, film of all, Primer directed by Shane Carruth, has plenty of paradox to consider. Check out Carruth's Upstream Color.