Neill Blomkamp’s 2013 science fiction parable splits humanity in two. The rich orbit in comfort, the poor grind on a broken Earth.

The film’s narrative may stumble, but its metaphors stay sharp and its imagery burns with relevance.

In 2154, Max Da Costa, played by Matt Damon (The Martian), is an ex-con factory worker poisoned by radiation.

With only days to live, he sets out to reach Elysium, a pristine orbital paradise whose machines can heal anything.

Jodie Foster (Silence of the Lambs, Taxi Driver) plays Secretary Delacourt, who orchestrates illegal coups to maintain the purity of her world, while Sharlto Copley’s Kruger hunts Max across the wasteland like a cybernetic predator.

From the moment Max is fused to an exoskeleton and storms the shuttles toward orbit, the film defines its stakes not as survival but as access, access to health, dignity, and life itself.

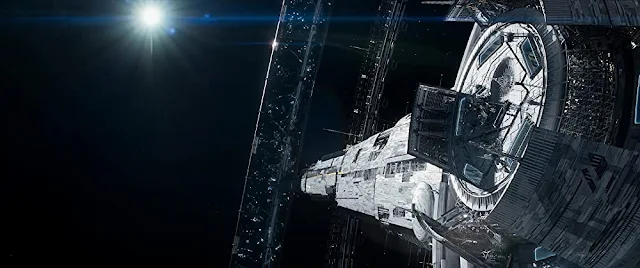

Blomkamp’s Los Angeles is a landfill of labor. Drone patrols buzz overhead, robots enforce quotas, and medical care comes in the form of pills dispensed by machines that cannot recognize human suffering. Every wide shot of Earth contrasts with the sweeping, sterile symmetry of Elysium’s gardens. The film’s dual imagery tells the story before the dialogue does: one half of humanity cleans the other’s windows.

When Max looks up at the ring in the sky, shimmering like a halo, the moment captures the central tension of the movie, the unreachable perfection that fuels both aspiration and despair.

Themes Grounded in the Plot

Class Division and Inequality

In the opening scenes, Max jokes with his co-workers about someday getting up there before a factory accident exposes him to lethal radiation. His death sentence becomes the perfect metaphor for systemic neglect, disposable labor feeding the machine of prosperity.

Meanwhile, on Elysium, citizens sunbathe under artificial skies, their conversations about illegals carried out in French over champagne. The contrast is unflinching; comfort requires cruelty.

Later, when desperate civilians launch shuttles toward Elysium and are gunned down midair, the metaphor tightens. Class division is enforced by orbital firepower. Every refugee turned to ash is another reminder that utopia depends on someone else’s apocalypse.

Healthcare Apartheid

The med-bays on Elysium can reconstruct tissue, erase cancer, even reset DNA. In one haunting sequence, a dying woman on Earth begs to use one for her child, only to watch the shuttle she boarded burn in the atmosphere. This technology, the film insists, could save billions, but it is coded to reject the poor.

The injustice is algorithmic, not accidental.

When Max hijacks the access codes from the corporate executive John Carlyle, the act is less a heist than a forced redistribution. He is not stealing wealth; he is stealing permission to exist. The image of his body being dragged through a med-bay scanner at the climax becomes both miracle and martyrdom, redemption paid in data.

Immigration and Border Control

Every attempt to reach Elysium mirrors real-world migration routes.

The shuttles launched from the Earth slums are packed like refugee boats, each carrying hope and desperation in equal measure. The film’s cold orbital interceptors blast them down without warning. The security drones that patrol the border act without empathy, machines trained to maintain purity through violence.

When Max finally pierces the atmosphere, he becomes a stand-in for all the voiceless migrants the film honors.

Corruption and Abuse of Power

Delacourt’s coup attempt exposes how easily moral codes bend under pressure. She reroutes a corporate program, orders civilian killings, and rewrites citizenship databases, all in the name of order.

When Kruger turns on her, seizing power for himself, the film completes the loop: power, unmoored from conscience, consumes itself.

In the background, Elysium’s politicians speak of policy integrity while playing tennis beside infinity pools. The hypocrisy is total, the system self-justifying. Blomkamp shoots these scenes in cold white light, purity as moral rot.

Technology and Responsibility

From Max’s exosuit to the med-bays to the weaponized drones, technology in Elysium is never neutral. When Spider, the hacker-revolutionary, hacks the citizenship algorithm, it is the first time in the film that technology serves justice. The sequence where the entire planet’s status updates to citizen is pure Blomkamp irony, redemption through code delivered by machines built for exclusion.

That moment reframes the story’s moral question. Progress is not what we invent but who we include.

Resistance and Collective Action

Max’s fight begins selfishly. He wants a cure for himself. But his transformation comes through connection, his bond with Frey and her sick daughter, his alliance with Spider’s underground, his final decision to upload the data that kills him but heals millions. His sacrifice fuses revolution with resurrection. The hacker’s crew, once seen as criminals, become architects of a new social order.

The film closes on Frey’s daughter waking in a med-bay, cured by a system that no longer discriminates. The rebellion succeeds not through destruction but through the rewriting of access itself. The system does not fall; it is repurposed.

Performances

Matt Damon gives Max a tired, working-class desperation that fits the film’s engine. Jodie Foster, seen in Contact and Panic Room, channels quiet fascism behind perfect diction. Sharlto Copley goes feral as Kruger, embodying a kind of corporate id unleashed on the poor. Each performance anchors a different side of the dystopian spectrum: survival, control, chaos.

Why It Matters Now

Every frame of Elysium echoes modern anxieties about wealth inequality, privatized medicine, and the politics of exclusion. When Earth’s citizens are finally granted access to Elysium’s med-bays, the film does not show jubilation. It shows relief. Blomkamp’s point is not utopia achieved, but injustice paused.

The system was always capable of fairness, it simply refused to activate it.

In today’s world of gated medicine, algorithmic borders, and engineered privilege, Elysium feels less like science fiction and more like prophecy with a pulse.

Elysium is messy, muscular, and moral.

It wraps its social critique in metal and sweat. Beneath the noise, it keeps asking one question worth revisiting: what good is progress if it forgets humanity on the ground?