1) Opening hook, the hats and the question

Those hats in the first shot are not decoration.

They are repetition made visible. Identical objects scattered across the ground like the leftovers of an experiment. The film opens by placing a quiet fact in front of you, then daring you to ignore it.

Then the question arrives, “Are you watching closely?”

On the surface, The Prestige is a rivalry story. Robert Angier and Alfred Borden are two magicians who turn professional jealousy into a private war. Under the surface, it is a screenplay that behaves like a magic act. It uses The Pledge, The Turn, and The Prestige as its operating system, not just as dialogue about stagecraft.

This breakdown treats spoilers as the point, read on at your peril...

2) Act I, The Pledge

The Pledge is where a magician shows you something ordinary and asks you to accept it as true. The film does the same thing with identity, rivalry, and time.

It gives you a courtroom first, Borden on trial, Angier watching, the machinery of judgment turning before you even understand the crime. That is deliberate misdirection. You are already looking at the wrong thing, because the film is already controlling what you think you need to know.

Then it moves backward into the “ordinary” world of apprenticeship. Angier and Borden are assistants under Cutter, part of a working machine of knots, cues, curtains, trapdoors. They look like two men on the same ladder.

The movie wants you to believe they share a craft and a future.

That normalcy ends in the water tank.

Julia, Angier’s wife, is lowered into the glass box. The knot matters. Borden ties it. She cannot get loose. The scene is shot like a contained nightmare, hands on glass, breath turning into panic, the rescue arriving too late.

Her death does not merely start the rivalry. It forges it.

Two philosophies, set early

Borden is technical, secretive, minimalist.

He respects the mechanism more than the applause.

Angier is theatrical, emotionally driven, obsessive.

He wants the audience to feel the trick in their ribs, even if it costs him.

The rivalry becomes personal because Angier’s grief needs a shape, and Borden is standing there, alive, refusing to give a clean answer about the knot. It becomes ideological because their approaches to illusion start to look like approaches to life.

It becomes professional because both men turn revenge into career development. Each new act is also a new weapon.

3) Act II, The Turn

The Turn is where the magician makes the ordinary object do something impossible. In this film, the object is identity. The impossible action is being one man and not one man, being present and absent, being seen and unseen.

The fulcrum is Borden’s “Transported Man.” The performance is clean, blunt, almost rude in its simplicity. Borden steps into a cabinet. Doors slam. Lightning flashes. He appears on the other side of the stage in an instant. The audience buys it. Angier cannot.

The escalation is not a blur. It is a staircase, and each step has a cost.

Sabotage becomes bodily cost

Angier sabotages Borden’s bullet catch, turning a stunt into a trap.

Borden survives, but he loses fingers. The film makes sure you see the injury not as abstract punishment, but as an invoice. Pain is now part of the magic economy.

Borden retaliates, targeting Angier’s work and reputation. The war shifts from “who is better” to “who can ruin the other faster.” Their craft becomes a delivery system for harm.

Doubles as a moral preview

Angier tries to copy the Transported Man with a double, Root. The humiliation is the point.

Root exists to be the dirty secret in the trick, the man stuffed into a cabinet so the star can take the bow. If Borden is obsessed with method,

Angier is obsessed with the moment the audience believes. Root is the human cost of that obsession.

The nested journals, answers that are not answers

The film then pulls a structural con that feels like revelation. Angier reads Borden’s diary. Inside it, Borden reveals that he has been reading Angier’s diary.

It feels like a hall of mirrors where each page promises the truth.

What it really does is give you the sensation of progress while tightening the blindfold. The diaries operate like patter. They keep your attention occupied with narrative voice and revenge games while the real method stays just off to the side.

Sarah and the clue disguised as “mess”

Borden’s home life looks unstable the first time. Sarah experiences him as alternating versions of the same man, tender one day, cold the next. T

he film stages these shifts in plain domestic spaces, quiet rooms, close conversations, the kind of scenes viewers often file as character drama rather than plot machinery. That is the disguise. What reads as emotional incoherence is actually structural evidence that identity is being rotated.

Tesla in Colorado Springs, a purchase that changes the ethics

Angier goes to Tesla believing he is buying a method.

A better cabinet.

A better trapdoor.

A secret that will make the stage obey him. What he gets is a machine that changes the story’s moral physics. The rivalry is no longer just about deception. It becomes about what kind of truth a machine can force into existence, and what kind of cruelty that truth permits.

4) Act III, The Prestige

The Prestige is where the magician brings it back and the audience pretends they did not want blood for it. The reveals here land because they do not float in as tricks. They land as the only way the earlier scenes could have behaved.

Borden’s secret, a twin and a shared life

Borden’s Transported Man is not a miracle. It is two people. He has a twin, and they live one life by switching roles, sometimes as Borden, sometimes as the quiet assistant “Fallon.” The trick is not the jump across the stage. The trick is the audience accepting that one identity can hold steady while the body behind it changes.

This reframes earlier scenes with hard clarity.

Sarah’s confusion becomes accurate perception. The alternating tenderness and coldness becomes two different men passing through the same marriage. The film’s talk of “living half a life” becomes literal household arithmetic.

It was always telling you the truth. It just trained you to hear truth as metaphor.

Angier’s method, replication and a nightly death

Tesla’s machine duplicates.

It does not transport.

Angier’s final act works because a copy appears elsewhere while another version is left behind. The film makes the horror land by returning to the water tank. The tank is not merely a prop from the origin tragedy. It becomes the mechanism of payment.

Angier’s performance requires a death every night.

The Angier who drops into the tank drowns. The Angier who appears across the stage lives long enough to accept applause.

The audience sees wonder. The film shows you the cost.

The frame story then snaps shut. Angier, using the identity “Caldlow,” frames Borden for murder. The trial is not a side route. It is the track the story has been laying from the start. Borden is hanged. The final confrontation is not twist for twist’s sake. It is consequence catching up in a locked room.

5) Clues and Chekhov’s fuses

The film plays fair, then uses your habits against you. Each clue is planted cleanly, then disguised through attention control, dialogue, and editing choices that encourage you to categorize the moment as “texture” instead of “evidence.”

The bird in the cage routine

What you assume: a charming trick, a lesson, a small family moment.

What it signals: wonder is often powered by cruelty. The child asking which bird lives is the moral question of the film hidden inside a simple routine. One bird dies. One appears. The audience accepts the trade because the presentation is sweet and quick.

How it is disguised: Cutter’s patter frames it as instruction, so you file it as exposition, not prophecy.

The bloodied finger

What you assume: rivalry escalating, injury as heightened stakes.

What it signals: sacrifice is not an idea here, it is currency. The film makes physical loss the first clear payment in the story’s ledger, preparing you for later, larger forms of self-erasure.

How it is disguised: the pain is loud, so you focus on shock instead of pattern.

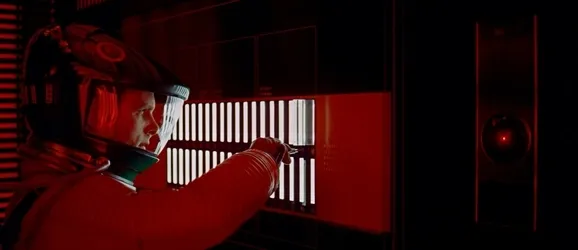

The identical hats at the beginning

What you assume: atmosphere, a mysterious image to set tone.

What it signals: replication. The film shows you the output of the machine before you understand the machine. It is the method hiding in plain sight.

How it is disguised: you are immediately yanked into trials, diaries, and rivalry, louder narrative objects designed to hold your gaze.

Water tanks, doubles, repeated staging, mirrored blocking

What you assume: motifs, period theatricality, recurring visuals.

What it signals: containers and replacements. The tank is consequence in physical form. Doubles appear first as labor (Root), then as camouflage (Fallon). Repeated stage positions work like visual rhymes, so the final act can land as the inevitable last beat of a pattern you have already seen.

How it is disguised: the film keeps giving you a more interesting thing to stare at, a new grievance, a new trick, a new betrayal.

6) Dialogue as an instruction manual

Cutter’s line, “You’re not really looking. You want to be fooled,” is not only theme. It is a functional note about how the film expects you to watch. The movie keeps demonstrating it. It puts Fallon in scenes where he looks like background. It shows Sarah naming the problem in plain language. It shows the hats. Then it distracts you with a trial, a diary, a machine, a new act. You cooperate because you want the trick to work.

Borden’s talk about sacrifice, about the price of a good trick, plays the same game. On first watch it reads like professional conviction. On second watch it reads like confession spoken in daylight. The script tells you the truth while training you to treat truth as metaphor.

7) Viewer experience, why it works

First watch feels like controlled disorientation. The timeline jumps. The story cross-cuts. You feel like you are chasing the plot. That sensation is designed. The film uses non-linear structure the way a magician uses misdirection. While you are re-orienting, it plants the real explanation in behavior, not in speeches.

Second watch reveals a lattice of tells. Sarah’s scenes stop reading as generic relationship strain and start reading as evidence. Fallon stops being wallpaper and becomes the hinge. The hats stop being mood and become math.

The movie transforms from puzzle to mechanism, and that is the point. The Pledge, The Turn, and The Prestige are not decoration.

They are the architecture that makes the story feel like a trick, then makes the ending feel like the only possible receipt.

8) Clean moral reckoning

Borden chooses a life that is technically pure and humanly mangled. His greatest method requires splitting identity, splitting love, splitting time, and calling the wreckage “commitment.” Angier chooses a life that is emotionally fueled and ethically scorched. He wants the audience’s gasp so badly he turns a performance into a recurring death.

Neither man is a simple hero. Neither is a simple villain. They are two forms of hunger, one for the perfect method, one for the perfect reaction, both willing to cash other people’s lives to pay for it. The film does not punish them with irony. It punishes them with consequence.